International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

When we think of human-centered design, there are two main types of design based on the target: private design, which targets individual interests and tastes, and public design, which targets optimal relationships among a larger number of people, mainly in public spaces. In the case of public design, because the target is a public space such as a train station, hospital, library, park, or school, the people who use the space can have diverse genders, nationalities, ages, and disability statuses. In other words, public design should be flexible enough to accommodate more “people.”

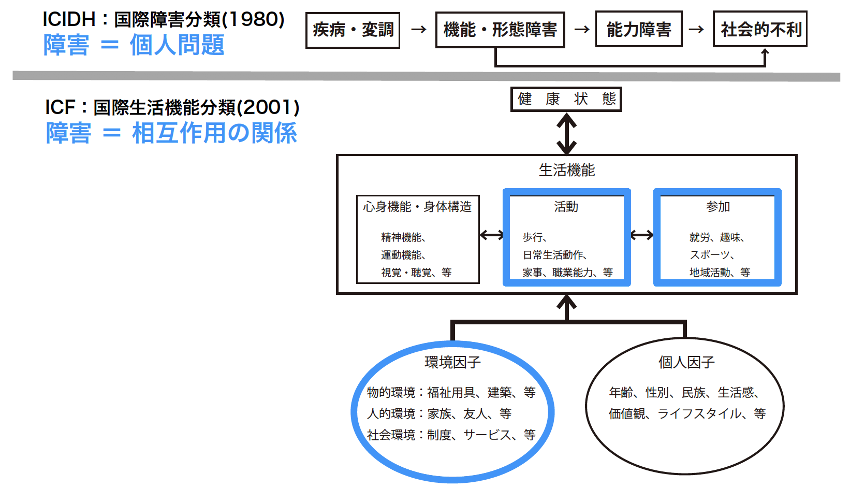

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in May 2001, is a “‘common language’ that represents the ‘whole picture of living.’” The ICF comprises the following elements: health status, life functions (physical and mental functions, physical structure, activities, and participation), and background factors (environmental and personal factors), and the combination of these elements results in a classification of about 1500 items. According to the concept of the ICF, each element is not unidirectional but comprises interactions.

However, the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH, 1980), the predecessor of the ICF, had a one-way approach to disability. In other words, it was structured in such a way that it assumed that a person born with a disability, such as a disease or modulation, would have functional and morphological impairments that would lead to disabilities and social disadvantages called handicaps. This model was groundbreaking in that it presented a “hierarchy of disability” that divided disability into three levels: functional and morphological disability, ability disability, and social disadvantage, but it focused on the idea of classifying the negative aspects of disability. The ICF, which replaced the ICIDH, was a major change in that it shifted the perspective to look at life functions from the positive side and added the perspective of “environmental factors” as influencing factors.

An “environmental factor” is defined as “the facilitating or inhibiting influence of features of the environment, such as the physical and social environment and people’s social attitudes.” According to the ICF (2002), examples include “social attitudes,” “the structure of buildings,” “legal and social structures,” “climate,” and “topography. The human, physical, and material environment includes “climate” and “topography.” The positive aspects of environmental factors are defined as “facilitating factors” and the negative aspects as “inhibiting factors. In other words, it has been officially stated that people’s “overall picture of living” can be better or worse depending on environmental factors.

Design is positioned as an “environmental factor” in the ICF. For example, in the case of a signage design to guide people to a destination, if the text information is carefully examined, a highly readable typeface is used, the color scheme is controlled, and a pictogram is included that can be understood without reading the text, the sign will qualify as an “environmental factor” that is easy to understand and will have a facilitating effect on the subject’s “activity” factor. The joy of being able to undertake an activity by oneself may increase one’s sense of self-affirmation and positively affect one’s mental and physical functions.

However, if the opposite is the case, “activity” will be limited and a functional impairment will be created. Again, to use the case of signage planning and design, if more text than necessary is included and is presented in a cluttered manner, if a typeface with low readability is used, if multiple highly saturated colors are used, or if a pictogram with an abstracted meaning that is difficult to understand is used, the sign will become an “environmental factor” that is difficult to understand and will have an inhibiting effect on the subject’s “activities.” This may have an adverse effect on the subject’s “mental and physical functioning” because of the decrease in self-confidence and self-affirmation because the subject was unable to undertake the “activity” by him or herself.

In this way, there is a close relationship between design and people, but we are rarely consciously aware of it.

In other words, if we consider the functional structure of human life based on the idea that people and design are environmental factors in ICF, then the role of design for people will naturally become clear. By specifically considering how the environmental factor of design interacts with the target “individual factor,” creating a design that can be inclusive of various people becomes possible.

(KUDO Mao)