Product Semantics

In many cases, a designed object points out its meaning to the people surrounding it. If this is the case, the object of design becomes a symbol. The idea that the ultimate goal of design is not to construct a real object, but to construct meaning through it, is called “semantics” in design.

In his famous 1984 article “Product Semantics: Exploring the Symbolic Qualities of Form,” Krippendorff argues that the meaning of the elements that make up a product is first realized through the physical and morphological characteristics of the elements, but that it is also determined by the relationship with the users of the product and the technical, psychological, and social context in which that relationship is situated. For example, a button, by its shape, means “push me” to the user, but when it is installed on the wall of an elevator, it means at the same time that the elevator will stop at that floor. The “sign” of the button and its meaning “referent” is mediated by the “thought” of the user who will press the button, based on the context in which it is located.

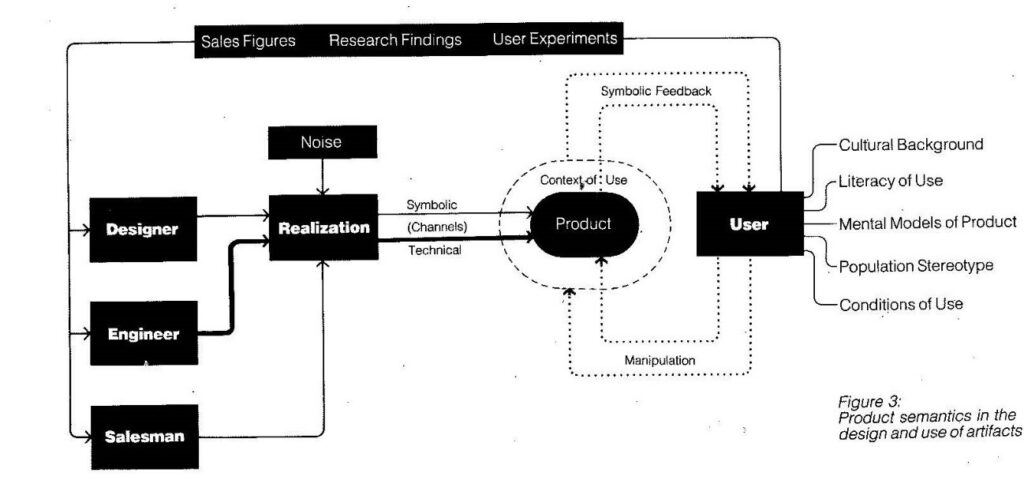

The user belongs to a certain cultural community insofar as he or she belongs to a certain society and observes certain customs. If this is the case, the designer cannot unilaterally define the meaning of the product to the users. The designer, along with engineers and salespeople, is only a communicator who arranges various elements so that users in the community can give meaning to the product and interpret it appropriately, and then readjusts the product and its context based on the results (see the figure below).

Regarding Krippendorf (2006), it seems that product semantics is based on the critique of managed society that flourished in Germany after the late 1960s. According to this critique, functionalism is linked to industrialization and capitalism, and designers as elites exercise total control over production and consumption, and thus over society as a whole. In functionalism, the components of a product have no independent meaning of their own, and the parts cannot exist apart from the whole, just as the organs and cells of a living organism are completely subordinate to it. Human beings, as an element of that subordinate system, become a cog in the whole.

For example, as long as a human body or a computer is functioning well, there is no need to be concerned about its components. However, when the function is impaired, if the elements that make up the product have no meaning, the user cannot communicate with them to repair or reassemble them. In functionalism, the internal structure of a product is a black box, and its design and maintenance are left to the designer who has the expertise. In semantics, not only designers but also users and other stakeholders can understand and enter into a product’s internal structure. Also, members of society should be able to have their meanings and maintain a certain level of independence to communicate with other components and weave the text of design freely, so to speak. In this respect, it is argued that product semantics is an idea that realizes the human-centeredness of design.

With the progress of electronics and computer technology, the target domain of design has expanded from the modeling of real objects to the interface between machines and humans. Under these circumstances, product semantics has grown to become one of the most important theories of design methodology since the 1980s, with the linguistics of Saussure and the semiotics of Ecko, Barthes, Morris, and Pierce as its background. Product semantics rejected the Cartesian and neo-positivist position that designers should guarantee a one-to-one relationship between symbols and their meanings in advance by introducing the user’s interpretive ability and contextual dimension into the design. At the same time, however, it is still an attempt to encompass the user’s behavior within the framework of the designer’s assignment of meaning, insofar as it ultimately aims to realize an appropriate relationship between the sign and its use based on feedback from the user and to avoid failure or confusion in the user’s interpretation of meaning.

(KOGA Toru)

Related Class

Design Literacy, Design Language I,II

References

- Krippendorff, K. & R. Butter (1984), “Product Semantics: Exploring the Symbolic Qualities of Form,” Innovation 3(2), 4-9, Spring.

- Krippendorff, Klaus (2006), The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation For Design, Taylor & Francis, New York. (クラウス・クリッペンドルフ(2009)『意味論的転回 デザインの新しい基礎理論』小林昭世ほか訳、エスアイビーアクセス)