Fordism

The further development of mechanization with industrialization had various negative effects, such as the destruction of nature, alienation of humanity, and widening social disparities. In response, systemic designs to eliminate these problems by pushing the mechanization of industrial products and production to the limit were developed from the latter half of the 19th century through the 20th century. A representative example is the design of automobiles and production systems proposed by Henry Ford.

In 1908, he developed a mass-produced model called the Model T Ford. Automobile production was realized through the division of labor using a line system rather than by craftsmen finishing each car one by one. The entire production process was divided as much as possible into simple work processes, with each unit taken on by its corresponding worker. By arranging the work process and worker pairs on the line, management could make the work process transparent, and freely edit and adjust the production process.

While the standardization of labor content forced workers to perform simple repetitive tasks, worker productivity increased dramatically. In 1914, Ford announced a significant increase in daily wages from $2.34, the average wage at the time, to $5.00, and a reduction in working hours from nine to eight hours per day.

The more units of the same model sold, the more the cost per unit would be reduced, thereby creating positive feedback to stimulate further demand. This dramatically reduced the price of Model T. The combination of lower product prices and increased worker purchasing power even enabled Ford workers to purchase cars they had produced on credit. By giving workers greater purchasing power, demand grew even more; the production of Model T Ford reached 15 million units within 19 years of its launch, leading to the motorization of American society.

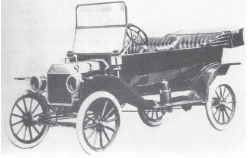

FIg.3 Model T tourer (1914)

出典: Ray Bachelor, Henry Ford Mass Production, Modernism and design, Manchester University Press, 1994, p. 23.

Consequently, the wealth of society expanded beyond comparison to pre-industrial times. This wealth even benefited a portion of the working class that supported society, creating a “mass” instead of a poor proletariat. This model of labor and production, in which the marginalization of labor through simple repetitive labor is supplemented by the return of wealth, is generally called “Fordism.”

In his biography, Ford consistently asserted a departure from the past and a triumphant leap into the future. He emphasized the machine’s power to break away from the traditions, cultures, disciplines, and religions of continental Europe. Ford’s mechanization efforts reconstructed the traditions, elegance, and organic nature of the old continent, showcasing the superiority and identity of New World America. For Ford, the designs of the product and production process are inseparable. According to him, the designer is an engineer who comprehends the internal logic of industrial products and systematically organizes the production process. Simultaneously, the designer functions as a managerial engineer, understanding not only how to place labor on the production line but also the intricacies of workers’ bodies and minds. Ford’s approach included manipulating wages to enhance work precision and motivate labor, with the results fed back to adjust worker involvement. Essentially, Ford himself played the role of both a manager and a product designer at the highest level.

On the one hand, Fordism contributed to the formation of an affluent mass society and laid the material foundation for a consumer society in the latter half of the 20th century. On the other hand, it became a model for imitation, notably by admirers such as Hitler. Hitler’s emulation of Fordism is evident in projects such as the construction of the Autobahn, development of Volkswagen, and establishment of the horrible factory at Auschwitz. (KOGA Toru)

(KOGA Toru)

Related Classes

- KIKAN education subjects, Design History

- Design Futures Course, Design Aesthetics

References

- Ray Bachelor, Henry Ford Mass Production: Modernism and Design, Manchester University Press, 1994.