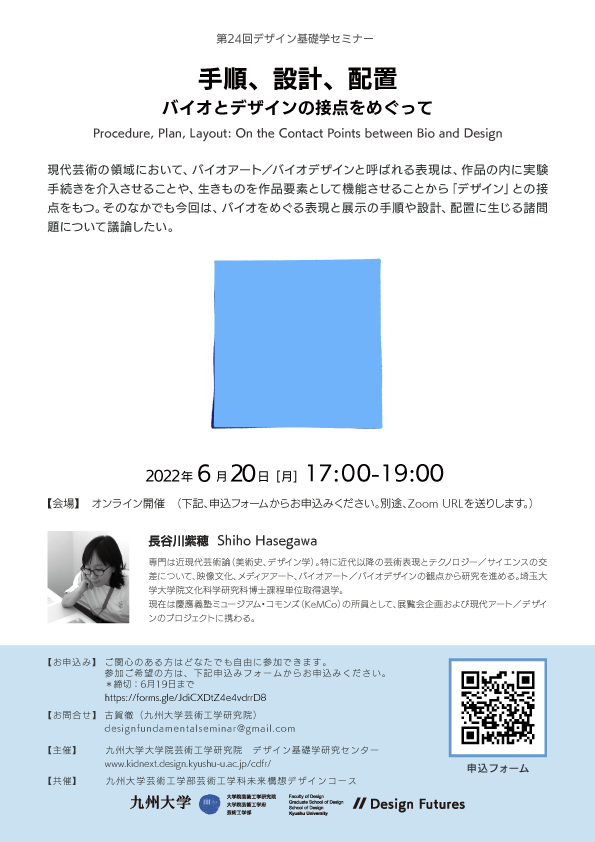

The 24th Design Fundamentals Seminar, “Procedure, Plan, Layout: On the Contact Points between Bio and Design”

The expressions known as Bio Art/Bio Design have several contact points with ‘design’ because of the experimental procedures involved in the work and the incorporation of living things as elements of the work. In this talk, we would like to discuss the various aspects of Bio Art/Bio Design works or displays regarding the procedures, plan and layout.

Lecturer

Shiho Hasegawa (KeMCo: Keio Museum Commons)

She specializes in modern and contemporary art theory (art history, design studies). She is particularly interested in the intersection of post-modern artistic expression and technology/natural science, from the perspectives of visual culture (film, video), media art, and bioart/biodesign. The completed doctoral programme at the Graduate School of Cultural Sciences, Saitama University without a degree.

Currently, she works on exhibition programmes and contemporary art/design projects as a curator/research fellow at Keio Museum Commons (KeMCo).

Date

Monday, 20, June, 2022 17:00-19:00 (Open at 16:50)

Venue

Online

Review

Bioart and biodesign may sound like a recent trend that has been gaining momentum over the past decade or so. However, Mr. Hasegawa’s lecture was divided into two parts, beginning with an exploration of historical examples of the connection between bio and design, and then moving on to the present by relating these examples to numerous recent works of art.

The first half of the lecture introduced a practice at the beginning of the 20th century that could be called proto-biodesign. The illustrations of Ernst Haeckel, a biologist who left behind detailed drawings of radiolaria and other organisms, are known to have had a considerable influence on Art Deco and Bauhaus practices from that time. And through the work of the botanist Raoul Heinrich Francé who popularized science, the architect Siegfried Ebeling proposed the inspirational concept of “architecture as a membrane”. According to Ms. Hasegawa, these examples from German-speaking countries are part of the “Biocentrism” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a conceptual framework that is being examined in recent studies of art and design history. Biocentrism, which developed in the form of a philosophy of life, organismic theory, and social reform movements based on them, used the aforementioned designs as a concrete procedure, in other words, individual designs functioned as an infrastructure of ideas and concepts.

The representative works of bio-art introduced in the latter half of the lecture confirm this understanding in the context of ongoing practice. Ms. Hasegawa links these works to the progress and popularization of the life sciences since the last century, the trend toward critical and speculative design that focuses on raising rather than solving problems, and the term “Anthropocene” which refers to the irreversible geological changes brought about by human activity. In other words, the terms that try to characterize these recent changes in time are the return of the “Biocentrism” of the present. Of course, we should be careful to note the differences in time and content, but it seems to me that, like the life-centered focus of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the specifications and modes of expression of bioart and design are required to function as an infrastructure linking natural science and means of expression in the current revival of the theme of “life”.

This is confirmed by the three examples discussed at the end of the lecture: “Culturing Cut” by Hideo Iwasaki, “Living Images” by Johanna Rotko, and “Borderless Bacteria/Colonialist Clash” by Ken Rinaldo.

According to Ms. Hasegawa, most bio-art works involve “setting up a living environment,” and in fact, “living” and “killing” are always accompanied by the display of the work. Specifically, the above works require glass containers such as Petri dishes as supports, and even other bioart works are often subject to contamination or leaks of the culture fluid during the exhibition period, and thus, they often face unique difficulties at the level of maintenance, management or storage. For the time being, let us try to understand these characteristics of the support as the physical closure of bioart.

On the other hand, the means to create these works are openly published as procedures and protocols on the artist’s website and in workshops. Not only at the level of these works, but also other energetic efforts of organizations such as BioHack Academy in Japan and Waag Futurelab in the Netherlands often focus on democratizing (bio)technology and “opening up” specific procedures and designs from closed institutional spaces such as biology and laboratories. As part of this project, during the lecture, Ms. Hasegawa actually introduced her practice of bioart production following the methods by Iwasaki and Rotko, which seems to me a natural scientist working on a reproduction experiment in a laboratory (to be sure, Ms. Hasegawa herself is not a scientist, but a researcher specializing in art and design history).

In the openness of these procedures, one can see an affinity not only with the so-called DIY culture, but also with the copyleft trend of actively releasing programming code on the web. Moreover, the openness of bio-art is not only a means of expression, but also connects it to various activities rooted in our daily life, such as cooking, meals, vegetable gardening, and plant cultivation. In fact, it is not difficult to see how Ms. Hasegawa’s imitation experience (or the “Procedure, Plan, Layout” in the title of this lecture) can be superimposed on familiar tasks, such as cooking while reading a recipe.

However, we should be cautious not to praise openness in a naive way or to place excessive expectations on it. Especially when dealing with the subject of “life”, there are obviously ethical issues involved in disclosing the process of manipulation, editing and production. In addition, in order to make it possible to share such work even in places where appropriate facilities and systems do not exist, such as universities, it is necessary to convert the specific individual procedures into a kind of script. This is one of the questions posed in the discussion that followed the lecture.

In short, the closedness and openness of bioart should be understood as two sides of the same coin of this trend, rather than as opposites that should be assigned to one or the other. Moreover, this ambiguity may not be unrelated to the well-known concept of the “Umwelt” by Jacob von Uexküll, which was introduced toward the end of the lecture. The concept of the Umwelt, which showed that even the smallest living creature, such as a tick or a flea, has its own unique perception of the world, is well known as a concept that points out the existence of a closed property of perception and cognition (a kind of bubble). However, this concept has been frequently reaffirmed in recent discussions related to bioart/design because it also offers an openness that breaks through the human-centeredness that has privileged our perceptions and subjectivity.

Then, how can we make it possible to open up the scripts of life and living, flexibly reconfiguring them each time, by directly confronting the physical characteristics of the phenomenon of life without confining ourselves to the given procedures? This was the question about bioart/design that emerged from the perspective of “Procedure, Plan, and Layout.”

(Nobuhiro MASUDA)