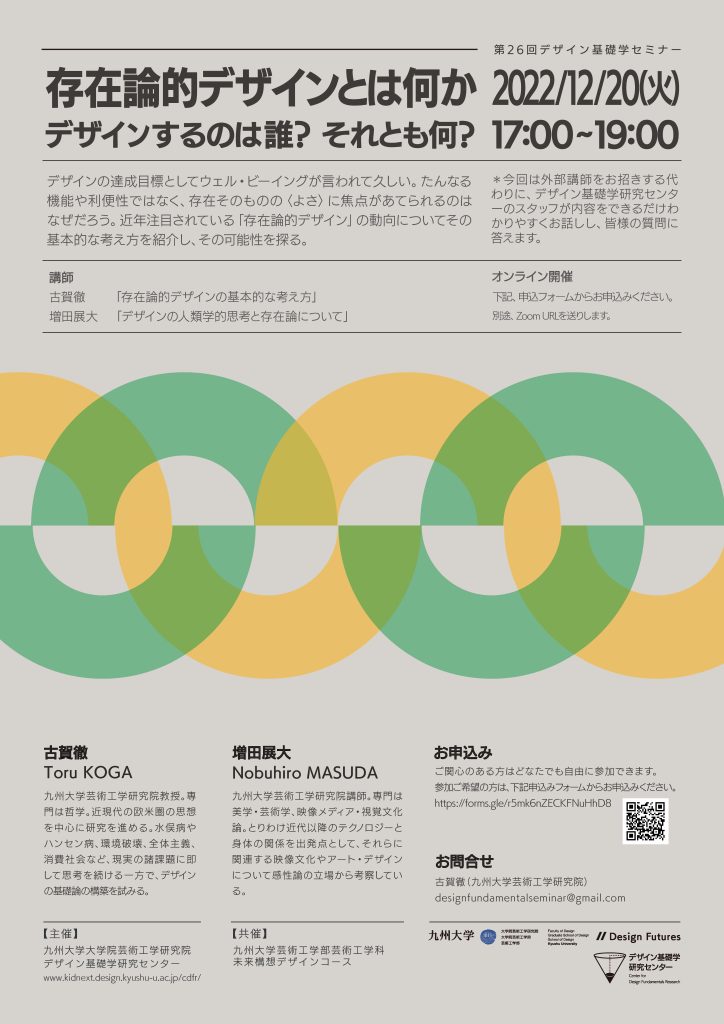

The 26th Design Fundamentals Seminar "What is Ontological Design? : Who or What designs?"

It has been a long time since well-being emerged as a goal to be achieved by design. Why is it that the focus is not on mere function or convenience, but on the “goodness” of being itself? This lecture will introduce the basic concepts of the “ontological design” trend that has been attracting attention in recent years, and explore its possibilities.

Lecturer

Toru KOGA (Kyushu University)

Nobuhiro MASUDA (Kyushu University)

Date

Dec 20th, 2022: Opens at 16:50 p.m, Seminar starts at 17:00 p.m. JST.

Online

*Instead of inviting an outside lecturer, the staff of the Center will talk about the content as clearly as possible and answer your questions.

Review

When we hear the term ‘ontology’, we tend to be somewhat defensive because of its esoteric image. Recently, however, it has become common to hear design theories described as ‘ontological’. Why and how has design, which is not limited to products and artworks but aims to solve problems in living environments and communities, come to be combined with ‘ontology’?

The 26th Design Fundamentals Seminar was held under the title, ‘What is Ontological Design: Who or what designs?’, with members of the Centre for Design Fundamentals Research introducing relevant discussions. First, Koga, who specialises in philosophy, highlighted an article by Anne-Marie Willis, ‘Ontological Designing — laying the ground’ (2006), as one of the sources, followed by Masuda, who introduced a relevant chapter from anthropologist Arturo Escobar’s book Design for the Pluriverse (2018) and opened the discussion to the audience after adding their reflections.

Behind Willis’ argument is, according to Koga, a critique of the scientism and positivism that dominated modern design, and an orientation towards a renewed approach to nature. Also called ‘transition design’, it is an attempt to critically overcome conventional Western/male/anthropo-centrism, based on criticism and reflection on the fact that unilateral technological development by humans has led to an environmental crisis. In parallel, one of the agendas of recent design has been the frequent use of the term ‘well-being’. Koga points out that the question of ‘a better way of being’ inevitably raises questions about what ‘being’ is and what it means to be ‘well’ in the first place.

It is no wonder then that Willis’s argument relies on Heidegger’s argument. This is because his philosophy investigated existence itself, which is made conscious when we become aware that we are ‘mortal beings’, even though we are not normally conscious of it. Referring to the famous discussion of this way of being in relation to tools (cups and hammers), Willis expanded it to the relationship between humans and artefacts (design). Humans does not only design artefacts unilaterally, but are also ‘designed’ by them in the sense that we are made aware of our own existence by the artefacts embedded in a particular environment. This point is the at the very heart of Willis’s argument and the following ontological design.

If, since the modern era, design has sought to dominate (nonhuman) objects by promoting rationalisation and efficiency with a specific intention and intent, this has in turn constituted a process of forgetting that humans are also designed by the things they produce (if we call the former ‘mechane’, which is promoted by modern science and technology, we can also distinguish the latter, technics in general integrated with life, as ‘techne’). Thus, the dominance of Western/male/anthropo-centrism to date is probably due to the repression of feedback from such production. In contrast, Koga calls for an ‘ontological virtuous circle’ that frees design from the intention and will of unilateral human domination of nature, and makes it conscious that the designs are proceeded by the non-human world. He identified as concrete examples of this the ‘KATTE-BASHI’ (Bridges with unknown administrators) left in various parts of Japan that continue to be used without anyone knowing who built them, or Akira Kurosawa’s film Ikiru (‘To Live’, 1952), which depicts a protagonist who breaks free from the bureaucratic work he had done until then when he becomes aware of his own mortality.

Escobar’s argument, introduced by Masuda, is also driven by an intense critique of modernity, although one less theoretically dependent on Heidegger. While referring to the arguments of Willis (and another design theorist, Tony Fry), Escobar traces the origins of ontological design back to theories of artificial intelligence (Winograd and Flores) and the concept of autopoiesis (Varela and Maturana) since the 1980s. These debates can be regarded as the source of ontological design because they were early attempts to break away from modern design (or Cartesianism), which took for granted the division between the subject of design practice and objects, such as nature and culture.

As Escobar noted, we can consider a recent smartphone as a case study. While their convenience and efficiency are touted, the fact is that we who use smartphones are often divided into polarised opinions (culture), and the technological developments required to do so have led to a global north/south divide (technology) and even excessive energy consumption and resource extractivism (nature)–problems to which we try to turn a blind eye. Nevertheless, given the impossibility of letting go of technology and returning to pre-modern regimes, how can design overcome the modern model, which is based on the opposition between the human subject and the object, such as culture, technology, and nature? In response to these questions, Escobar also summarises the idea of ontological design and calls for a shift to what he calls a ‘pluriverse’. Whereas modern society, which aims at development through science and technology, has in fact by now fallen into the ‘one-world world’, its counterpart, the pluriverse, is positioned as consisting of multiple self-emergent/autonomous communities, each made up of human and non-human beings. The emphasis of his argument is also on ‘Vivir Bien’, or well-being.

Thus, Escobar also emphasises the relationships between humans and communities as ‘designed beings’ for the transition to the pluriverse, but what is important is that these relationships include not only humans and their productions but also the nonhuman, specifically technology, animals, and plants. This point may be linked to recent trends in anthropology, such as actor-network theory (Bruno Latour), which focuses on the agency of non-human beings, and multispecies ethnography (Ana Tsing), which rethinks human beings in terms of their interactions with other species. After confirming this, Masuda identified an example of the transition to a multispecies world in the essay ‘Wasteland Ecology‘, which points to the complex relationship between humans, technology, plants, animals, and microorganisms using the unique history of a Danish waste disposal site as a case study.

The seminar, led by two leading theorists of ontological design, attracted a diverse range of participants from the fields of enterprise and administration, in addition to those from universities, and the discussions that followed were very lively. The topics included, for example, the question of the existence and role of the ‘designer’ when non-human animals and plants are regarded as the agency, and the possibility of combining design with Heidegger and other related philosophical traditions (such as Kitaro Nishida’s union of subject and object, or the recent discussion of object-oriented ontology). It is not possible to introduce the details, but if these discussions helped to deepen critical thinking about design at the same time that they broke down and concretised the complexities of ontology, it may be said that they also promoted a ‘virtuous circle’.

Acknowledgment: This project was conceived following discussions with Takahito Kamihira, who spoke at the 25th Design Fundamentals Seminar. We would like to thank him for his later review of the contents of this seminar.